Novel transparency information reveals that this good news doesn’t always translate into savings. Below, we rely on a unique data set from Turquoise Health to examine how much four national commercial health plans—Aetna, Anthem, Cigna, and UnitedHealthcare—paid hospitals for Avastin and its two most significant biosimilar competitors.

As we demonstrate, health plans pay hospitals far above acquisition costs for biosimilars. What’s more, plans can pay hospitals more for a biosimilar than for the higher-cost reference product. The U.S. drug channel system is warping hospitals’ incentives to adopt biosimilars, while simultaneously raising costs for commercial plans.

The namesake of my alma mater once said: “Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants.” What would happen if we disinfected the entire channel?

HERE COMES THE SUN

Turquoise Health graciously provided DCI with a sample from its Drug Primary Rates data, which combines negotiated rates reported by hospitals and by payers.

Turquoise Health draws in part on data from CMS’s Hospital Price Transparency Final Rule, which requires hospitals to report previously non-public details about their third-party contracts with commercial health plans. The data also rely on the Transparency in Coverage rule, which requires payers to report in-network rates for covered items and services. Turquoise Health’s full dataset includes over 6,000 hospitals and health systems. To learn more about accessing these data, visit turquoise.health.

We focused our analysis on Avastin (bevacizumab) and its two largest biosimilar competitors. Avastin was among the drugs with the highest pre-rebate share of commercial medical benefit drug spending in 2019 (prior to the launch of biosimilars). Avastin now faces five biosimilar competitors. Two of these products—Mvasi and Zirabev—now account for more than 80% of the unit market share in the bevacizumab market.

Our sample included the August 2024 payment amounts negotiated between the top 26 non-profit or government-owned cancer hospitals and four national commercial health plans—Aetna, Anthem, Cigna, and UnitedHealthcare. Not all hospitals had published rates for each payer for each product. Information about the computation of the negotiated rates is not publicly available. Commercial payment rates exclude the value of any rebates that manufacturers paid to the plans.

The wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) list price for the three products were comparable. Avastin’s WAC was $3,188. The biosimilars’ list prices were discounted: Mvasi was $2,791 (−12% less than Avastin), and Zirabev was $2,454 (−23% less than Avastin).

Turquoise Health data also included each product’s ASP payment limit under the Medicare Part B program. The ASP equals a drug’s list price minus all price concessions to U.S. purchasers (excluding sales that are exempt from Medicaid “best price” calculations and sales to other federal purchasers). ASP approximates the commercial pricing of a provider-administered drug, so this measure includes the effect of commercial rebates. A drug's ASP will be higher than the net price received by the manufacturer.

For more details on the distribution and reimbursement of provider-administered drugs, see Chapter 3 of DCI’s 2024-25 Economic Report on Pharmaceutical Wholesalers and Specialty Distributors

ISLAND IN THE SUN

The chart below summarizes the results of our analysis.

[Click to Enlarge]

Observations:

- Hospitals earn significant markups over the ASP. The dashed red line shows the ASP for each product. On average, payments far exceeded the ASP for each product. Across all payers and health systems, hospitals received 203% more than Avastin’s ASP, 262% more than Mvasi’s ASP, and 219% more than Zirabev’s ASP.

- Insurers pay different prices for the same drug. For Avastin and its two primary biosimilar competitors, Aetna paid higher rates than the other three payers.

Consider payments for Avastin, which averaged $6,552 (Aetna) to $3,542 (Anthem). Average payments for Mvasi ranged from $3,007 (Aetna) to $1,536 (Anthem), while average payments for Zirabev ranged from $1,932 (Aetna) to $1,275 (Cigna).

Note that these commercial payment rates exclude manufacturer rebates. For 2023, 35% of employers and 67% of commercial health plans reported receiving rebates for provider-administered injectable and infused drugs billed under the medical benefit. (source.) The prevalence and value of medical benefit rebates have grown as innovator products have begun competing with biosimilar products.

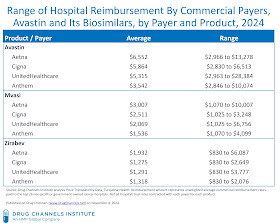

- Insurers pay vastly different prices for the same drug to different hospitals. The table below shows the average, minimum, and maximum reimbursement by the four payers for each of the three products.

[Click to Enlarge]

The variation in reimbursements for the same drug astounded us. For comparable quantities of Zirabev, hospitals were paid from $830 (Cigna) to $6,087 (Aetna), while they got paid from $1,025 (Cigna and Anthem) to $10,007 (Aetna) for Mvasi.

We also found numerous instances of excessive biosimilar reimbursement. In about one out of five cases, total hospital reimbursement for the Mvasi biosimilar was greater than the brand-name drug's list price!

- Manufacturers earn a minority of the third-party payers’ drug reimbursement. Contrary to popular belief, hospitals—not drugmakers—keep about 80% of what insurers pay for these provider-administered drugs. Discounts from the 340B Drug Pricing Program help hospitals earn more than the drug’s manufacturer does.

These mark-ups shouldn’t surprise anyone who understands the buy-and-bill market.

Commercial payers often reimburse hospitals based upon a negotiated percentage of charges—a hospital’s self-defined list price for a drug. Basically, a hospital marks up a drug to create a highly inflated “charge.” It then discounts the charge to a rate negotiated with the payer. Unlike public drug benchmarks, hospital charges are arbitrary and do not have to follow any particular methodology

Such reimbursement approaches permit hospitals to get paid two to three times as much as other sites of care—and to inflate drug costs by thousands of dollars per claim. See Section 3.2.2. of DCI’s wholesale industry report for more on this phenomenon.

We would expect transparency to reduce price variability. In other words, hospitals above the market average will decrease prices to remain competitive, while those with below-average rates would increase prices after discovering that they have been charging too little. A recent Turquoise Health white paper suggests that prices are converging in some markets, with the added benefit that overall prices have dropped slightly. However, we don’t yet know how these dynamics will play out in markets where a hospital has a dominant market position and therefore has little incentive to reduce prices.

Despite the biosimilar results documented above, America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) continues to tout biosimilars as the solution to “out-of-control prescription drug prices.” The Turquoise Health data suggest that commercial plans need to spend some time soaking up the sun.

The contents of this post reflects the views of Drug Channels Institute and do not necessarily reflect the views of Turquoise Health.

No comments:

Post a Comment