Today, I want to highlight three significant—and presumably unintended—drug channel consequences from the hastily-passed IRA legislation. These include disruption to the now-booming biosimilar market, the prospects of physician/hospital vertical integration that will raise commercial healthcare costs and expand 340B, and the need for complex new processes to administer the IRA's lower pharmacy reimbursements.

I can only barely scratch the surface in this article, so feel free to share your own thoughts in the comments below or on social media.

At this point in our country’s history, you might think Congress would have learned the immutable law of 730-page bills: Legislate in haste, repent at leisure.

Meet the IRA

The Inflation Reduction Act was signed into law by President Joe Biden on August 16, 2022. This law includes numerous changes to prescription drug pricing in the Medicare program:

- Manufacturers must engage in a price negotiation process for drugs used in Medicare Parts B and D

- Manufacturers must pay mandatory rebates for Part B and D drugs whose prices increase more quickly than the rate of inflation

- Plans and manufacturers will have much higher liabilities for costs in the Medicare Part D benefit.

- Providers will receive different payment rates for single-source Part B drugs and biosimilars

- Price Negotiation, Medicare Rebates, and Benefit Reform, King & Spalding

HMMM…

Despite significant uncertainty about the law’s implementation, I see at least three potential unintended consequences that have not yet received much attention:

1) Biosimilar launches will get weird—and less frequent.

The IRA will create novel circumstances governing biosimilar launches. It will therefore change the biosimilar market in ways that are currently hard to predict, with associated uncertainty for manufacturer and channel profits from these products.

A key unknown revolves around decisions by manufacturers of reference products and biosimilars. Section 11002 of the IRA contains a “Special Rule to Delay Selection and Negotiation of Biologics for Biosimilar Market Entry” that can delay a biological drug’s negotiation process for up to two years.

The delay is based upon a complex set of conditions, including whether the Secretary of HHS determines that there is a “high likelihood” a biosimilar product will be licensed and marketed with the two years after which a drug is eligible for negotiation. This determination does not require that the biosimilar be interchangeable with the reference product.

Notably, the manufacturer of a biosimilar must request this delay and is also responsible for providing (as-yet-undefined) “clear and convincing evidence” of a forthcoming launch. If the biosimilar does not launch, then the reference product manufacturer can be subject to retrospective rebates.

Consider what could happen. In some situations, the reference product’s manufacturer may expect competition with a biosimilar to generate higher profits than the profits that would result from a price negotiated with or established by CMS. Therefore, the manufacturer may alter its patent and litigation strategy to encourage biosimilar entry. We may even see highly novel strategies, such as “pay-for-launch” agreements between the manufacturers of the reference product and its biosimilar.

It is also conceivable that the manufacturer of the reference product could launch its own non-interchangeable biosimilar version, which could deter other manufacturers from launching biosimilar products.

In other circumstances, the reference product’s manufacturer may attempt to maximize profits by engaging in negotiations with CMS as a way to deter a biosimilar from entering the market. The government-negotiated price may be lower than the reference product’s current price, but higher than the price were the manufacturer to face competition from one or more biosimilar products. However, the reference product manufacturer could end up with a much higher market share that it would have when competing with multiple biosimilar versions. Total spending could be higher than it would have been had the reference product faced competition from multiple biosimilars.

Over time, we will likely see fewer biosimilar launches and therefore lose the benefits of competition. Today, prices in therapeutic classes with biosimilar competition have declined by 60% or more in less than three years. Legislators do not seem to have contemplated biosimilar market disruption in their rush to pass the IRA.

A key unknown revolves around decisions by manufacturers of reference products and biosimilars. Section 11002 of the IRA contains a “Special Rule to Delay Selection and Negotiation of Biologics for Biosimilar Market Entry” that can delay a biological drug’s negotiation process for up to two years.

The delay is based upon a complex set of conditions, including whether the Secretary of HHS determines that there is a “high likelihood” a biosimilar product will be licensed and marketed with the two years after which a drug is eligible for negotiation. This determination does not require that the biosimilar be interchangeable with the reference product.

Notably, the manufacturer of a biosimilar must request this delay and is also responsible for providing (as-yet-undefined) “clear and convincing evidence” of a forthcoming launch. If the biosimilar does not launch, then the reference product manufacturer can be subject to retrospective rebates.

Consider what could happen. In some situations, the reference product’s manufacturer may expect competition with a biosimilar to generate higher profits than the profits that would result from a price negotiated with or established by CMS. Therefore, the manufacturer may alter its patent and litigation strategy to encourage biosimilar entry. We may even see highly novel strategies, such as “pay-for-launch” agreements between the manufacturers of the reference product and its biosimilar.

It is also conceivable that the manufacturer of the reference product could launch its own non-interchangeable biosimilar version, which could deter other manufacturers from launching biosimilar products.

In other circumstances, the reference product’s manufacturer may attempt to maximize profits by engaging in negotiations with CMS as a way to deter a biosimilar from entering the market. The government-negotiated price may be lower than the reference product’s current price, but higher than the price were the manufacturer to face competition from one or more biosimilar products. However, the reference product manufacturer could end up with a much higher market share that it would have when competing with multiple biosimilar versions. Total spending could be higher than it would have been had the reference product faced competition from multiple biosimilars.

Over time, we will likely see fewer biosimilar launches and therefore lose the benefits of competition. Today, prices in therapeutic classes with biosimilar competition have declined by 60% or more in less than three years. Legislators do not seem to have contemplated biosimilar market disruption in their rush to pass the IRA.

2) Physician practices will accelerate their consolidation into health systems and hospitals—ultimately raising costs for commercial plans and expanding 340B.

Over the past 15 years, hospital outpatient departments have been displacing physician offices in the market for provider-administered drugs. This shift has occurred primarily because hospital and health systems have been acquiring physician practices. We expect that the IRA will trigger more rapid vertical integration of hospitals and the practices that administer specialty drugs.

The IRA will trigger this consolidation activity in two ways.

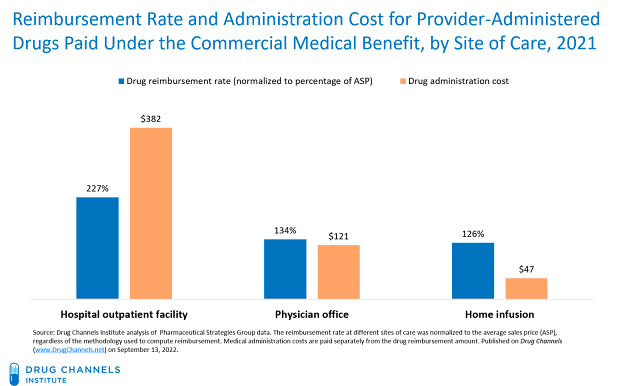

For 2021, commercial health plans reimbursed hospitals at the equivalent of 227% times a drug’s ASP and paid administration fees of $382. Physician offices were reimbursed at the equivalent of only 134% times a drug’s ASP and were paid fees of $121. Home infusion received lower drug reimbursement rates and lower administration fees. These data are consistent with the figures from 2017 that I discussed in Still Possible: Hospitals Overcharge Health Plans for Specialty Drugs. There is no provision in the IRA or elsewhere that would alter or address this reimbursement gap.

The IRA will trigger this consolidation activity in two ways.

- Beginning in 2028, HHS will have the authority to negotiate a “maximum fair price” (MFP) for single-source Medicare Part B drugs and biologics. Provider reimbursement for these products will be set equal to 106% of the MFP, rather than 106% of the average sales price (ASP). The MFP will likely be lower than the ASP, so the dollar value of add-on payments will decline. Physicians will find practice ownership less attractive and will look to sell their practices.

- At the same time, the IRA will increase the financial advantages of participating in the 340B Drug Pricing Program. That's because 340B hospitals will be able to purchase products at the lower of the 340B ceiling price and the MFP. (Hospitals account for nearly 90% of all 340B purchases.)

Physician practices, however, will not have access to lower 340B pricing. 340B hospitals will be the providers best able to financially survive with lower Part B payments. They will become the primary buyers of physician practices with significant drug spend. Purchases by the acquired practices will become eligible for 340B pricing.

[Click to Enlarge]

For 2021, commercial health plans reimbursed hospitals at the equivalent of 227% times a drug’s ASP and paid administration fees of $382. Physician offices were reimbursed at the equivalent of only 134% times a drug’s ASP and were paid fees of $121. Home infusion received lower drug reimbursement rates and lower administration fees. These data are consistent with the figures from 2017 that I discussed in Still Possible: Hospitals Overcharge Health Plans for Specialty Drugs. There is no provision in the IRA or elsewhere that would alter or address this reimbursement gap.

3) Implementing MFPs will require a new approach for managing reduced pharmacy reimbursements from Part D plans.

Under the IRA, HHS has the authority to negotiate an MFP for a limited number of single-source drugs and biologics used in the Medicare Part D program. Section 1198 states the negotiated price—the amount that a Part D plan pays to a pharmacy for having dispensed a drug to a Medicare beneficiary—“shall be no greater than the maximum fair price.” Section 1193 of the IRA further directs manufacturers to provide the MFP to eligible individuals at the point of dispensing or administration.

Alas, the legislation does not specify how the manufacturer should implement a system to provide this price only for Medicare patients, nor does it contemplate what will happen when pharmacies get lower prescription reimbursements for these prescriptions.

One logical option would be some sort of chargeback process. Traditional chargebacks permit discounted acquisition costs for a pharmacy’s or provider’s entire purchases. The difference between the price paid by the pharmacy and provider and the wholesaler’s acquisition cost is subject to a chargeback transaction under the process we outline in Section 3.1.4. of our annual Economic Report on Pharmaceutical Wholesalers and Specialty Distributors.

The current chargeback approach could be adapted to the implementation of the IRA. The system would require the development of a new type of per-prescription, patient-specific chargeback discount that is specific to eligible Medicare patients. It would also require new technology standards and a novel transactional infrastructure to implement a per-prescription chargeback system. (Long time readers may recognize echoes of 2018’s A System Without Rebates: The Drug Channels Negotiated Discounts Model.)

Another possibility will be to build upon the split-billing approaches used for contract pharmacies in the 340B Drug Pricing Program. See Section 11.5.3. for our follow-the 340B-dollar flowchart in 2022 Economic Report on U.S. Pharmacies and Pharmacy Benefit Managers.

Wholesalers, PBMs, and technology companies are among the multiple entities who are likely to compete to administer MFPs into the channel. Channel participants will seek to develop a new set of fee-based services for manufacturers, while the technology vendors will be eyeing a lucrative new market.

Not complex enough for you? Then don’t forget that for 2024, plans will also begin applying pharmacy DIR price concessions to the negotiated price in Part D!

Alas, the legislation does not specify how the manufacturer should implement a system to provide this price only for Medicare patients, nor does it contemplate what will happen when pharmacies get lower prescription reimbursements for these prescriptions.

One logical option would be some sort of chargeback process. Traditional chargebacks permit discounted acquisition costs for a pharmacy’s or provider’s entire purchases. The difference between the price paid by the pharmacy and provider and the wholesaler’s acquisition cost is subject to a chargeback transaction under the process we outline in Section 3.1.4. of our annual Economic Report on Pharmaceutical Wholesalers and Specialty Distributors.

The current chargeback approach could be adapted to the implementation of the IRA. The system would require the development of a new type of per-prescription, patient-specific chargeback discount that is specific to eligible Medicare patients. It would also require new technology standards and a novel transactional infrastructure to implement a per-prescription chargeback system. (Long time readers may recognize echoes of 2018’s A System Without Rebates: The Drug Channels Negotiated Discounts Model.)

Another possibility will be to build upon the split-billing approaches used for contract pharmacies in the 340B Drug Pricing Program. See Section 11.5.3. for our follow-the 340B-dollar flowchart in 2022 Economic Report on U.S. Pharmacies and Pharmacy Benefit Managers.

Wholesalers, PBMs, and technology companies are among the multiple entities who are likely to compete to administer MFPs into the channel. Channel participants will seek to develop a new set of fee-based services for manufacturers, while the technology vendors will be eyeing a lucrative new market.

Not complex enough for you? Then don’t forget that for 2024, plans will also begin applying pharmacy DIR price concessions to the negotiated price in Part D!

BUT THAT’S NOT ALL…

The IRA will have numerous other unintended consequences.

For instance, the Congressional Budget Office projects that the IRA’s inflation-rebate provisions would “increase the launch prices for drugs that are not yet on the market relative to what such prices would be otherwise.”

What’s more, the IRA will skew R&D budgets away from small molecule drugs—particularly for diseases that target older populations or require step-wise development like cancer. Eli Lilly CEO Dave Ricks recently outlined these realities. Hat tip to Peter Kolchinsky of RA Capital for his valiant—but ultimately unsuccessful—efforts to prevent this particular unintended consequence.

There are a litany of other complex issues facing market access and formulary development. For instance:

- Some therapeutic categories will have drugs subject to an MFP competing with drugs that offer conventional rebates and fees. Will Part D plans and PBMs prefer drugs with rebates (DIR) over drugs that have an MFP?

- How will a brand-name product with an MFP affect rebates for other products in the same therapeutic class?

- Once Part D plans have greater liability for spending, how much will they lobby for the ability to crank up utilization management tools?

- Will stand-alone prescription plans (PDP) become less economically viable, thereby driving even more seniors into Medicare Advantage plans?

I’m only skimming the surface of the many unknown and potentially problematic aspects of the IRA. Stay tuned for the forthcoming 2022-23 edition of our wholesale industry economic report, where I’ll examine the impact of the IRA on wholesale distribution. I’ll be addressing the IRA’s impact on pharmacies and PBMs in the 2023 edition of our pharmacy/PBM report.

As my friend Mike Marks is fond of saying: “A learning experience is what you get when you expected something else.” I expect we’ll all be savoring many learning experiences in the years to come.

CORRECTION: The original version of this article incorrectly stated that the manufacturer of a reference product could delay the negotiation process by launching a biosimilar of its own product. However, several better informed Drug Channels' readers pointed me to Section 11002, which specifically prohibits this option.

As my friend Mike Marks is fond of saying: “A learning experience is what you get when you expected something else.” I expect we’ll all be savoring many learning experiences in the years to come.

CORRECTION: The original version of this article incorrectly stated that the manufacturer of a reference product could delay the negotiation process by launching a biosimilar of its own product. However, several better informed Drug Channels' readers pointed me to Section 11002, which specifically prohibits this option.

No comments:

Post a Comment