A new report draws some unexpected conclusions about pharmacy profits when a prescription benefit plan sponsor combines a “transparent” pass-through Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) contract with a preferred network design. See The Value of Alternative Pharmacy Networks and Pass-Through Pricing: An Actuarial Analysis. (free download) The study was conducted by Milliman, an actuarial firm, and sponsored by Restat, a privately-held PBM.

A new report draws some unexpected conclusions about pharmacy profits when a prescription benefit plan sponsor combines a “transparent” pass-through Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) contract with a preferred network design. See The Value of Alternative Pharmacy Networks and Pass-Through Pricing: An Actuarial Analysis. (free download) The study was conducted by Milliman, an actuarial firm, and sponsored by Restat, a privately-held PBM.The surprising conclusion about a preferred network design with transparency? A majority of the savings come from reduced pharmacy margins, not from reduced PBM margins. Milliman estimates that the pharmacy gross profit per script would drop by 78% for brands and by 50% for generics. Yikes!

While these reductions seem awfully large to me, this report is a useful thought experiment that should spark some critical thinking by plan sponsors, PBMs, and pharmacies. The detailed estimates are pictured below. Let me know what you think in the comments.

Last February, I asked: Why do pharmacy owners care about PBM transparency? The Milliman study suggests an important corollary: Be careful what you wish for, lest it come true.

BACKGROUND

Restat offers a preferred pharmacy model to self-insured employers called Align, which allows consumers to reduce their out-of-pocket costs at certain network pharmacies. (Full disclosure: Retstat is a past and future sponsor of Drug Channels. However, this sponsorship did not influence my comments.)

The growth of preferred pharmacy networks such as Align is one of the four major trends for the PBM and pharmacy industry in 2011. Other examples of preferred networks include the Humana Walmart Preferred Rx Plan and the Caterpillar-Walmart-Walgreens network model. Walmart advocates narrower pharmacy networks in a white paper released last June. (See Walmart's Pitch for Smaller Pharmacy Networks.)

Pharmacies participating in Restat’s Align program include the usual suspects—Walmart, Target, and many supermarkets—along with a number of regional chains. Surprisingly, the network includes 2,600+ independent pharmacies through the participation of McKesson’s Health Mart franchise members.

BTW, the report has a fairly neutral explanation of PBM revenue sources and contract structures (pass-through vs. spread pricing) starting on page 7. See Exhibit 23 (page 30) of The 2010-11 Economic Report on Retail and Specialty Pharmacies for my own estimates of the Big Three’s profits for a spread pricing model by pharmacy format and type of drug.

METHODOLOGY

Milliman began with top-line average savings for employers from Restat’s Align program, which are reportedly 38% savings for retail generic prescriptions and 10% savings for retail brand prescriptions. I computed the savings using “Net Cost to Employer (Employer pays PBM, net of rebates)” on page 23 of the report. Restat confirmed to me that these figures represent real-world savings seen by its Align clients.

The study’s authors then estimated the source of per-script savings by estimating the flow of the drug dollar from manufacturer to consumer, across all drug channel participants (PBM, pharmacy, and wholesaler). See page 20 for Milliman’s methodology. Note that the estimates do not rely on claims data from Restat clients.

PHARMACY PROFITS

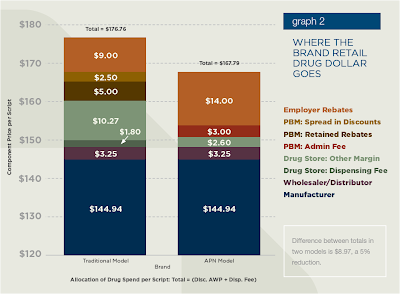

Milliman modeled the comparison between a “traditional model” (open network) and an “Alternative Pharmacy Network." Keep in mind that the estimates incorporate two different effects:

- Competition among pharmacies to participate in the network

- Payer visibility into PBM and pharmacy spreads

And here is the brand retail prescription result. A pharmacy’s per script gross profit—spread (“other margin”) plus dispensing fee—drops from $12.07 to $2.60 (-78%).

And here is the brand retail prescription result. A pharmacy’s per script gross profit—spread (“other margin”) plus dispensing fee—drops from $12.07 to $2.60 (-78%). WHAT DO YOU THINK?

WHAT DO YOU THINK?If we assume a 70% generic dispensing rate, the average gross profit per script goes from $15.07 to $6.44.

Is this a realistic figure? Do employers think that this level of profit is reasonable for a pharmacy? Will pharmacies willingly bear the brunt of transparency? Are narrower networks gaining momentum or not?

Bonus question: Can you tell a green field from a cold steel rail?

Adam, how very timely is this post!

ReplyDeleteWhat's most unbelievable is the incentive to dispense generics has gone into the toilet! Hooray for Merck and Pfizer. How terribly bad this is for the payer community.

With further thought, maybe it's not so bad. Let the consumer make the decision if they want a brand or generic through the use of huge copay spreads b/w branded/formulary vs generic products. It's not the decision of the pharmacist who potentially has an economic tie to the Rx with our current system.

Transparency is good. We all deserve to see what things cost, and what they sell for. Yet the dollar margin s/b realistic and cover the expenses to keep the drugstore running.

Again, we're all still looking for a new reimbursement system with true, honest/transparent benchmarks, and dispensing fees which can pay our bills.

Adam:

ReplyDeleteThank you for the highly informative post.

My comment relates to restricting member pharmacy access via contracts that at least in “any-willing provider” jurisdictions may need to allow any “willing” pharmacy to participate if it accepts the pricing model.

If plan sponsors and their PBMs/MCOs are forced to open up networks to more retail community pharmacies, then the reward for accepting lower reimbursement, the increased revenue(spillover) from foot traffic in return for lower Rx reimbursements is diluted as that foot traffic would be spread over more and more participating pharmacies.

Culturally, we are a society that prizes convenience and choice above else. Employees complain to HR and Benefits personnel about any restrictions on their ability to see a doctor or visit a pharmacy. Therefore, regardless of the “savings”, for political reasons, companies are generally unwilling to restrict access to the neighborhood pharmacy in favor of a cross-town rival.

This push-back on HR is called “member noise” and it is a courageous and/or suicidal HR VP that ignores such noise in favor of an incremental savings for the company.

I wonder how this model will play in Poughkeepsie, Peoria, Providence and elsewhere. In the age of 24 hour pharmacies and one-stop shopping convenience, how many employees will change their pharmacy allegiances because their HR department offers a benefit choice to do so?

The consumerism that is so rampant in the USA always seems to push HR departments to provide for more choice and open network designs. Americans do not like being “fenced in”. Absent substantially lower deductibles and co-pays -why will consumers flock to such a benefit design in a cafeteria plan shop? EPOs and HMOs had their days in the sun back in the 80s and 90s but the societal push back in part related to restrictions that limited choice of providers and allegedly also operated to limit patient access and the quality of services therein provided.

Rob Fellman

So we continue to ignore the "elephant" in the room? The Brand manufacturer; the largest contributor to the price; the most profitable business entity; and whose price in the APN Model equation does not decrease.

ReplyDeleteRob,

ReplyDeleteAs I understand Align, it is not a "restricted" network because consumers do not have to change pharmacies. Instead, it is a "preferred" model. The consumer continues to have a choice of pharmacy but also has financial incentives to use the particular pharmacies that offer a cost or performance advantage to the payer. Restat tells me that there are 15,000 pharmacies in the network.

If you pay cash for your prescriptions, then feel free to shop anywhere. But once you ask someone else to pay, then why is it controversial for that payer to influence your decision?

Adam

Philosophy: I agree that the existing PBM model is greatly flawed.

ReplyDeleteDecreasing access to decrease cost will achieve only minimal reduction in overall health care cost. An Access Based network as “described by Restat” is equivalent to a National one payer system in that it may slightly lower cost but will it deliver a quality product to all.

In the Wal-Mart limited access model white paper they compared their program to purchasing janitorial services on bid. However, will Wal-Mart stay with a low cost janitorial service that does a poor job of cleaning their bathrooms? No they will not.

I do agree that a limited access network design is the road to take. However, the access should be based on quality and total health care cost reduction, a “Centers of Excellence” (COE) network. A network of drug distribution that states it will make prescriptions passing through their portals perform to make the clients healthy and more productive workers.

Not Access, Not price, but performance: performance that yields healthy employees is the only way to lower health cost both drug and medical.

Numbers: If it were true that Restat “only” grossed $3.00 per Rx the stock holders would revolt.

Jim Fields ApproRx

Adam:

ReplyDeleteThank you for the clarification in regard to the network operations.

With 15,000 pharmacies concentrated primarily in MSAs, the network would seemingly offer good geographic coverage and choice for members. That said, how much additional spillover foot traffic do these "in-network" pharmacies really derive from network participation. Generally healthcare providers do not accept lower reimbursement for goods and services unless it can be demonstrated that non-participation is harmful or that participation is helpful.

Given the concentration of pharmacies in MSAs - I wonder the extent to which pharmacies may be cannabalizing their own margins through participation in these networks. That said, if per store revenue per square foot increases for soft goods and scripts dispensed simarly increase and this incremental revenue growth coincides with participation, then I think there is an extremely compelling business case for pharmacies to participate.

However, what prevents any competing pharmacy left out in the cold from later seeking to join the network by accepting the lowered reimbursement and then recovering its lost revenue in whole or in part from other nearby in-network pharmacy providers if the network does not contractually restrict pharmacy composition to only a select panel within a given zip code or geomapped area.

I do understand that this benefit designs help to eliminate past practices wherein generic reimbursement to pharmacies often exceeded the actual acquisition cost of the generic drugs and I do not think creating cost efficiencies in supply and distribution for third party payers is or should be controversial - I merely recognize how politically charged pharmacy reimbursement is at the state and Federal levels in our litigious society and I therefore seek to understand such arrangement to estimate how vested interests may respond to market trends that may threaten their sustained profitability. Depending on whose ox is being gored, the controversy surrounding a cost saving proposal is usally simply a matter of economic self-interest and supply chain position and perspective.

Rob,

ReplyDeleteAs a card-carrying economist, I tend to think that almost everything is driven by "economic self-interest and supply chain position and perspective." ;)

Adam

Interesting report, thanks for the heads-up. I tend to agree with you re: preferred networks. One comment on your blog suggests Americans love choice. But if they have to foot more of the bill, their choice will be influenced, I believe.

ReplyDeleteAt the end of the day isn't restat just saying: 1) we will take less than other pbms to do your business, and 2) if you prefer pharmacies we can get better deals there?

Always enjoyable to see what you're focused on.

I hope that ReStat and others will continue to push limited or preferred networks. It's about time. We can't continue to have lower prices and have all our options. Something has to give.

ReplyDeleteThe sad thing about this document is that it was a long winded and flawed explanation to drive how a simple model that there is an economic benefit to adopting a preferred pharmacy model.

Here's my more detailed comments - http://georgevanantwerp.com/2010/12/16/alternative-pharmacy-network-whitepaper/.

George

I agree with Mr Van Antwerp that Milliman paper uses a lot of words to reach an obvious conclusion, but I feel the underlying reason for the papers efforts was to further encourage the use of PBMs. The paper uses a highly inflated profit margin of the existing PBM model, reduces those margins only slightly, leaving plenty of room for excessive profits during the Restat adjudication process.

ReplyDeleteRegarding Mr Van Antwerps bullets points:

Number 3) Repackaging does occur and occurs frequently, allowing a new NDC to be assigned to the product and often a new AWP.

Number 7) Though the P&T process “in or out” is clinical in nature the tiering and/or copay process once on the formulary is not clinical but rebate driven

Number 8) 35% rebate retention is low not high. As a small PBM we once used a large PBM as a rebate manager. In law suit brought within the last 5 years we forced this PBM to divulge rebate information to all their clients using them as a rebate manager. We receive this report today on quarterly basis and the rebate retention still exceeds 90%.

I do agree that a limited access network design is the road to take. However, the access should be based on quality and total health care cost reduction, a “Centers of Excellence” (COE) network.

I also believe that the community pharmacist is the route to take to achieve this overall reduction in health care cost.

Jim Fields RPh CFO ApproRx

This entire discussion completely misses the genesis of the majority of PBM profits....all a health plan/employer needs to do is to negotiate out the spread on generics, using fixed price knowledge...no discussion of transparency, no "pass-through," just demand a fixed value for each of the 2500+ generic gcns...purchaser sets the rules, vendors will follow....

ReplyDeletethis is from one who knows

Anonymous of 01/20/11 is correct....Cost Plus or Acquisition plus pricing will financially aid retail pharmacy, employer/patient, and communities,

ReplyDeleteFirst let me state that I am coming at this from a broad perspective. I have consulted for large PBMs, I have been part of audits of large PBMs,(including Medco and CVS/Caremark), I am now the owner of Health Insurance Agency, A third party administration agency, a PBM, 2 health clinics, and 2 pharmacies all very small granted, but this combination and background has allowed me insights not available to many.

ApproRx defines AqP’s specific value as the price the average pharmacy, 62,000 Rxs per year, pays for a drug from our average wholesaler, ApproRx defines average wholesaler as the average price from ABC, Cardinal, and McKesson for a particular drug.

Generic profits: the math here is definitely “Fuzzy Math” the reason being that it is not math, most generic profits are made in words, i.e. the contract. Specifically the definition of generic is manipulated, as is MAC and AWP, to get desired profit numbers, thus you cannot look at the average cost of generics mathematically because in all contracts this ability is eliminated by legalize.

Remember that PBMs do not actually purchase generics; for the most part they subcontract with their networks do that, a $210.9 billion channel compared to $53 billion for mail order. NOTE: Not all mail order pharmacies are PBM owned, thus at best PBMs represent 25 percent of channel competition. You can rest assured that the other %75 of the channel will continue to compete vigorously for the generic dollar.