Friday, December 15, 2006

Santa's Supply Chain

Let's wrap-up the year with some homegrown Drug Channels supply chain humor, straight from the pages of The Wall Street Jovial:

I will be back with my outlook for 2007 on January 2. Until then, have a great holiday!

Adam

Wednesday, December 13, 2006

Catching up on AMP and PDMA

1. Roundtable: Deficit Reduction Act (Pharmaceutical Executive, Nov. 2006)

I believe that 2007 could go down as the year of Average Manufacturer Price (AMP). I still believe that AMP will ultimately have a much bigger impact than many people expect. (See my June post McClellan and the magic AMP for background.) This roundtable article has some good insights about:

- The class of trade issue

- The use of AMP for rebates vs. reimbursement

- Implications of a public release

2. Injunction May Slow Momentum for RFID E-Pedigrees (RFID Update, Dec. 12 2006)

Check out this interesting article on PDMA that quotes Jayne Juvan, my favorite (and the only?) healthcare law blogger, as saying: "Ultimately, the courts tend to favor the government in cases such as this that allege Equal Protection Clause and Due Process Clause violations when the rational basis test applies." She's referring to the RxUSA et al case against the FDA.

The article also calls Drug Channels a "pharmaceutical law blog," which almost offends me. Maybe I should sue?

Sunday, December 10, 2006

Thank You for Buying Counterfeits

Well, head over to Jayne Juvan’s surprisingly readable legal analysis of the recent injunction entitled RX USA Wholesale v. Department of Health & Human Services: A Legal Perspective. Jayne is a fan of yours truly, so allow me to return the compliment and suggest you read her thought-provoking perspective. She concludes: "Despite this victory, the Plaintiffs in this case have a long way to go, as the litigation only began a few months ago and this is only one hurdle among many that the Plaintiffs must overcome."

I was immediately reminded of a scene from the very funny movie Thank You for Smoking in which the main character (a Washington lobbyist) is asked by his son: "Dad, why is American government the best government?" Without looking up, Dad the lobbyist quickly replies:"Because of our endless appeals system." (This is a great DVD and an even funnier book, so make haste and pick it up today.)

More prosaically, I believe that the very concept of “pedigree” may need to be reconsidered. Counterfeits enter via diversion in the secondary market. But counterfeit sellers require counterfeit buyers, a problem that is not directly solved by pedigree requirements of the PDMA.

In Our Demand Side Counterfeit Drug Problem, I describe three rules that must be followed for pedigree to make the supply chain safer:

- Pharmacy buyers must demand pedigree documents (electronic or paper) from wholesalers and be able to validate the authenticity of these documents.

- Pharmacy buyers must only purchase from wholesale distributors in the “Normal Distribution Channel” or wholesale distributors that are willing and able to supply pedigree.

- Consumers must (a) refuse to do business with any pharmacy that does not adhere to the preceding two rules, and (b) be able to validate a pharmacy’s compliance with these rules.

In response, the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy launched a new website in November called http://www.dangerouspill.com/, complete with self-congratulatory press release. Like its PhRMA-sponsored counterpart http://www.buysafedrugs.info/, the NABP site aims to educate consumers about the dangers of buying counterfeits.

Business Week also jumped on the bandwagon this week with Bitter Pills, an article outlining the dangers of ordering drugs from “shady online marketers.” (Good tip!) Business Week helpfully portrays the sordid world of online pill sales as a cartoon, although I don't think my kids will be seeing that cartoon on Nickelodean following The Fairly Oddparents!

These worthy efforts aim at consumers. But I must note that the NABP and PhRMA sites sidestep the culpability or responsibility for pharmacy buyers to follow safe sourcing practices. Yes, I know that the NABP Model Rules outline various “Criminal Acts” associated with knowingly handling counterfeit drugs. Even legitimate pharmacists sometimes purchase in the secondary market. For example, a 2004 study found that two-thirds of hospital pharmacy directors use secondary wholesalers as a resource to obtain needed supplies during a product shortage. (Source: A research article published in the American Journal of Health-System Pharmacists.)

The industry sites do not help consumers identify legitimate pharmacies nor do they provide a way to validate that a pharmacy is behaving ethically in its sourcing practices. “End-to-end” visibility is a long way off, so we in the industry must confront the pharmacy buyer problem sooner or later, regardless of the endless appeals that are likely to dog the FDA's attempts to implement the PDMA.

Wednesday, December 06, 2006

The Impact of the PDMA Injunction

The FDA has not updated their PDMA resources page as of this morning, so it’s unclear what their formal strategy will be. Since I’m not qualified to opine on the FDA’s legal options, I’ll focus on a few business implications for manufacturers and wholesalers.

Manufacturers

This injunction should serve as a channel strategy wake-up call to manufacturers. In my opinion, senior executives in commercial operations at pharmaceutical companies should push their trade relations teams to develop formal channel management strategies. Frankly, the PDMA’s conception of “authorized distributor of record” is somewhat simplistic relative to channel management practices in other industries. (More on this topic below.)

I also want to reinforce my belief that manufacturers should invest more resources into gaining visibility into the movement of their product from factory to patient. Despite the RFID hype, the U.S. is still many years from a functional track-and-trace infrastructure, which was defined by Dr. von Eschenbach as “from the assembly line to the dispenser” at the NACDS/HDMA RFID conference. (See The FDA on PDMA.)

The Secondary Market

Let’s not delude ourselves –secondary markets will always exist when there are opportunities to arbitrage price differences between identical products being sold at different prices in different markets. In Europe, this arbitrage occurs as products are diverted across national borders and is called parallel trade. (See London Calling: Fake Drugs Get Real.) In the U.S., arbitrage also occurs as products are diverted between different classes of trade. Check out this graphical depiction of gateways into the U.S. supply chain.

While diverted or resold products are not necessarily counterfeits, all counterfeits enter via diversion in the secondary market. As the Chairman of the Subcommittee on Criminal Justice, Drug Policy and Human Resources noted in November 2005: “The FDA confirmed with Subcommittee staff that drug diversion was the entry point for every case investigated by that agency involving counterfeit drugs going into legitimate pharmacies.” Thus, any wholesaler operating in the secondary market should reasonably expect a higher level of scrutiny over their activities.

Secondary wholesalers

I am impressed by this legal victory, especially given my earlier skepticism. However, secondary wholesalers should recognize that manufacturers in many industries can and do legitimately limit the number of intermediaries that are authorized to sell its products. For example, Apple only allows iPods to be sold through authorized resellers.

The degree of distribution selectivity is a strategic channel design issue for a manufacturer, ranging from a single distributor (exclusivity) to an unrestricted number of distributors within a given market (intensive distribution). There is a large body of academic research on distribution channel selectivity in economics, law, and marketing supporting these channel strategies. Fans of academic jargon may enjoy reading an academic research paper on the topic that I published almost 10 years ago (available here), although the data did not include the pharmaceutical industry.

Given my comments about diversion above, secondary wholesalers must be willing to provide complete transparency to manufacturers about their business practices and product sources. Legitimate secondary wholesalers must be willing to clearly and unequivocally demonstrate how they differ from the unsavory wholesalers that traffic in potentially counterfeit product.

Big 3 Wholesalers

I believe that the introduction of Inventory Management Agreements (IMAs) and Fee-for-Service agreements now limit product leakage into the grey market, closing a significant entry point for counterfeiters. Drug makers literally pay for greater product security by purchasing data from wholesalers to monitor orders, inventories, and product movement in real-time.

In addition, wholesalers such as AmerisourceBergen Corp (ABC) and Cardinal Health Inc (CAH) publicly renounced secondary market sourcing, the HDMA tightened its membership requirements, and major pharmacy chains such as CVS committed to secure sourcing. My conversations with executives at the big 3 wholesalers – McKesson Corp (MCK), Cardinal Health, and AmerisourceBergen – have convinced me that these companies are genuinely committed to a secure supply chain.

Two more things

- Before we let the rhetoric about “extinction of small distributors” get out of hand, I must ask: How come we have not heard about secondary wholesalers going out of business in Florida after the July 1 implementation of state-level pedigree? Just wondering…

- I must be touching a nerve on this topic because a few individuals prefer to insult me via private emails. One of these fellows (“D.K.”) is too cowardly to disclose his affiliation in this matter. I have posted my opinions for all to see. Perhaps he will open himself up to the same scrutiny by posting a (non-anonymous) comment on this blog.

Tuesday, December 05, 2006

It's Official: PDMA is Back On Hold

See my post from last Friday -- No PDMA for You! -- for background. Then read Federal Injunction Will Delay Part of Drug-Tracking Law in today's Wall Street Journal, which states:

"In a surprising decision that strikes a blow against Food and Drug Administration efforts to curb counterfeit drugs, a federal judge granted an injunction that delays part of a long-stalled drug law that was to have taken effect Friday of last week.

Yesterday, U.S. District Court Judge Joanna Seybert of the Eastern District of New York sided with a group of drug wholesalers who argued that the law is in breach of equal protection and due process because it requires certain recordkeeping of some wholesalers but not others, according to lawyers for both sides of the case."

BTW, Heather Won Tesoriero of the WSJ and I appear to be the only people writing about this topic. Although that's surprising given the hype leading up to Dec. 1, I think of it as just one more good reason to tell your friends in the industry to read this blog. 'nuff said.

Monday, December 04, 2006

Sloppy reporting about Wal-Mart

Last Thursday's New York Times included some very sloppy reporting about Wal Mart Stores Inc (WMT). See Side Effects at the Pharmacy. (The story was widely syndicated, so here's an alternate link: Side Effects at the Pharmacy.)

The article questions the profitability of Wal-Mart’s program by incorrectly interpreting prescription data and then quoting a “consultant” with an undisclosed bias against Wal-Mart. This type of shoddy reporting only further confuses the debate about health care spending.

Since the New York Times’ editors read this blog, allow me to clear the air a bit by answering four questions:

- How busy is an average Wal-Mart pharmacy? (A: A lot less than an average Walgreens)

- How many more prescriptions did the $4 generic program generate? (A: About 16% more)

- Did Wal-Mart have $31.5 million in extra dispensing costs? (A: Nope.)

- Why was the Times so unbalanced? (A: Piling on?)

Q1: How busy is an average Wal-Mart pharmacy?

As a baseline, let’s estimate the typical volume at a Wal-Mart pharmacy in 2005.

- According to Drug Store News, Wal-Mart’s 2005 Rx sales were $11.036 billion.

- The average price per script in the mass merchant pharmacies was $62, implying that Wal-Mart dispensed 178 million prescriptions in 2005.

- Wal-Mart had 3,289 stores with pharmacies (per DSN).

After a little math, I estimate that the average Wal-Mart store dispensed 148 prescriptions per day in 2005 (assuming 365 selling days per year). For comparison, the same calculation for Walgreens yields an estimate of 270 prescriptions per pharmacy per day in 2005.

Q2: How many more prescriptions did the $4 generic program generate?

According to Wal-Mart’s Nov. 16 press release: “To date, as new states have been added to the program, 2.1 million more new prescriptions have been filled in those states as compared to the same time periods last year.”

- As of November 15, the generics program was available in 2,507 Wal-Mart stores.

- Stores were added on four different days (9/21; 10/6; 10/19; and 10/26). A calendar and some math shows that Wal-Mart had almost 65,000 total available selling days for the $4 generics program in these stores.

- Wal-Mart’s claim of “2.1 million more new prescriptions” translates into almost 15,000 new prescriptions per available selling day, or 32 new prescriptions per store per available selling day.

In other words, the average Wal-Mart pharmacy’s daily volume has increased by 22% (32/148) from September 21 to November 15.

However, IMS data indicates that total prescription growth was 6% from mid-September to mid-November 2006 versus the same period last year.

Therefore, it appears that Wal-Mart’s $4 generic program has added about 16% in real incremental prescription volume to the typical Wal-Mart pharmacy.

Q3: Did Did Wal-Mart have $31.5 million in extra dispensing costs?

The New York Times pooh-poohs the program, noting “…Wal-Mart might be able to declare the overall program profitable only by spreading the costs well beyond its pharmacy ledger.” The reporter then quotes “a pharmacy consultant in Stoughton, Wis.” named Ed Heckman: “But other costs, including store overhead and pharmacists’ paychecks, can add as much as $15 to the cost of dispensing a prescription, Mr. Heckman said. ”

Let’s see…2.1 million prescriptions @ $15 equals …$31.5 million!! So the program must be a boon for all of those pharmacists who are working extra hours, right?

Wrong. Total volume at a Wal-Mart pharmacy has gone up by about 32 new prescriptions per day – about 2 per hour given typical store hours. Marginal (incremental) overhead costs are probably $0.00 for an average Wal-Mart pharmacy. Following Mr. Heckman’s quote, the reporter notes that “selling drugs at $4 might be well below cost for many pharmacies.” Perhaps, but probably not for Wal-Mart.

Q4: Why was the Times so unbalanced?

I’m afraid I can’t really answer this question. Perhaps they are piling on after the post-election bashing given by Senator Barack Obama and former Senator John Edwards?

Nevertheless, I feel compelled to note that the New York Times failed to disclose a major conflict behind the quote above about costs. Mr. Heckman is not just a “pharmacy consultant,” but also President of PAAS National, a company that is "supported and endorsed by the NCPA” (the National Community Pharmacists Association). According to its website, PAAS also operates the Community Pharmacy Contract Clearinghouse for NCPA.

I note this lack of disclosure because NCPA has been a very outspoken critic of Wal-Mart. Check out the rather unambiguous titles of NCPA’s press releases "analyzing" Wal-Mart's $4 program:

- Wal-Mart Generics Program: Less Than Meets The Eye (11/21/06)

- Wal-Mart PR Stunt Goes Nationwide (10/19/06)

- Wal-Mart Pulls Another Fast One (10/5/06)

- Wal-Mart Offers Up Classic Bait-and-Switch (9/28/06)

Hmmm, wonder what NCPA really thinks?

---

Anyway, this point of this post is simply to highlight that sometimes what passes for analysis in the mainstream media is really just opinion. Or as U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan famously quipped: "Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts."

Friday, December 01, 2006

No PDMA for you!

Looks like the PDMA will not be going into effect after all.

Looks like the PDMA will not be going into effect after all.I've been skeptical about the injunction filed by a group of secondary wholesalers to stop implementation of the pedigree requirements of the PDMA on Dec. 1. (See The FDA on PDMA and Channel Conflict as Pedigree Looms.)

But on Thursday, Magistrate Judge Kathleen Tomlinson recommended that a preliminary injunction against the Department of Health and Human Services and the FDA be granted. See the Wall Street Journal story Judge Rules on Long-Delayed Drug Law. (Fans of legal reasoning will surely enjoy the full injunction report and recommendation.)

Sunday, November 26, 2006

Of Spammers and Senators

If so, then you should check out The Philadelphia Inquirer’s fascinating 8-part series about a father-son duo that imported bulk drugs from India and then fulfilled orders for online pharmacies. Check it out here: http://go.philly.com/drugnet

Here’s how it worked:

- To avoid U.S. Customs, which targets small pill packages from overseas Web sites, Dr. Brij Bansal in India and his son, Akhil Bansal in Philadelphia, shipped millions of pills in bulk from Delhi to their Queens, N.Y., distribution center.

- American consumers, responding to spam or using Google to search for drugs, placed a credit-card order with a Web site. The Web site charged the consumer's credit card, then forwarded the order to the Bansals’ operations in Agra, India, and Queens.

- Immigrants at the Queens depot fulfilled the order, stuffing pills inside envelopes for UPS pickup. Within a day or two, UPS delivered the pills to the consumer's doorstep. Every few weeks, the Web-site operators wired payment to one of Akhil Bansal's bank accounts.

Nevertheless, I’d be willing to wager that manufacturing conditions at Dr. Bansal’s Indian operation did not quite meet FDA GMP standards. No mention of distribution best practices in the Queens warehouse, either.

The Return of Cosmic Irony

And in a strange bit of cosmic irony, the Associated Press put a prescription drug reimportation story on the wires Thursday. See New push to allow imported drugs expected in Congress.

Unfortunately, Senators Vitter and Nelson remain blissfully ignorant about the dangers posed by allowing consumers to source products outside of legitimate domestic channels. Some questions for them:

- Where will "Canadian" pharmacies source products from? Hopefully not people like the Bansals, but we’ll never really know.

- How will we stop consumers from buying from “bad” pharmacies? I bet the Bansal’s online pharmacy customers had Canadian flags on their websites.

- Who will regulate non-U.S. pharmacies? The FDA does not regulate or control the buying practices of domestic retail pharmacies. Fans of reimportation have yet to explain how a U.S. government agency will ensure the safety of foreign sources. And keep in mind that the DEA, not the FDA, went after the Bansals.

--

On a happier note, Jayne Juvan, the legal brains behind Juvan's Health Law Update, just made my Monday morning by recommending this blog to her readers. Thanks, Jayne! I'll do the same and suggest that you all check out Jayne's weekly legal update.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

The Attack on Generic Profits in Drug Channels

Today’s Wall Street Journal has a very good overview of key issues for the generic industry, such as biogenerics and the FDA’s generic approval process. See Democrats’ RX? Generics.

However, I wonder if this renewed political focus on generics will ultimately reduce the profits of pharmacy chains and wholesalers. Companies that could be affected include CVS Corp (CVS), Walgreens (NYSE WAG), and McKesson Corp (MCK), to name just a few.

As faithful readers of this blog know, the supply chain – wholesalers, retail pharmacies, and mail order – get a larger share of total prescription drug revenue from generics. Profits on generic drugs now subsidize the retail and wholesale distribution of much more expensive branded products. (See my May post Will unbundling crush pharmacy profits?).

How profitable are generics? For fun (?), I went back to the 2004 CBO report Medicaid’s Reimbursements to Pharmacies for Prescription Drugs, which studied Gross Profits per Script (GPS) for pharmacies under the Medicaid system. Note that the study refers to GPS as “markups” and excludes any co-payments received from patients.

Gross Profit Per Script for Pharmacies in Medicaid (2002)

- Brand-name Drugs = $13.80 (14%)

- Older Generic Drugs (pre-1997 launch) = $9.90 (70%)

- Newer Generic Drugs (1997 to 2002) launch = $32.10 (70%)

In other words, filling a generic Medicaid prescription earned a pharmacy $18.30 more per script in 2002. These data come from 2002, so they go a long way to explaining why the new Federal Upper Limit for generic reimbursement under Medicaid will shift to Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) + 250% rather than an AWP-minus model. (See McClellan and the Magic AMP and AWP Ain’t What Matters for background.)

The channel's genertic profits are also under visible attack in the minds of consumers. As I pointed out yesterday, Wal Mart Stores Inc (WMT) is aiming at the pharmacy industry’s weak spot, encouraging pharmacies to argue that consumers should ignore price. (See Wal-Mart Raises the Stakes.)

But let's not forget that these profit margins provide powerful incentives for generic substitution by the channel, which has in turn lowered drug spending by employers and the government. Key scenario questions that I am now considering with my clients:

- How will manufacturers and payers manage the costs of getting products from the factory to the patient?

- What will happen to the retail and wholesale channel if generic margins come down?

- What parts of the supply chain will retain reasonable profit opportunities?

Hey, I’m just one voice out there, so please don’t forget Newton’s Second Law of Consulting: For every expert, there is an equal and opposite expert.

Have a Happy Thanksgiving!

Monday, November 20, 2006

Wal-Mart Raises the Stakes

Wal Mart Stores Inc (WMT) just expanded its $4 generic program to 38 states and more than 3,000 pharmacies. See Wal-Mart Adds 11 More States To $4 Prescription-Drug Plan. Check out Bob Nease’s succinct overview of Wal-Mart’s updated list at Libratto.

Most interesting is the fact that Wal-Mart added pravastatin (generic Pravachol), a $2.3 billion blockbuster for Bristol-Myers Squibb Co (BMY) in 2005. Sounds like The Empire Strikes Back scenario in which I predicted that the list would be broadened to include blockbuster generics. In an online poll, that scenario got 56% of the votes vs. 44% for Much Ado About Nothing. (I stopped the voting after two weeks, so last week’s news did not affect the results.)

According to Wal-Mart’s press release: “To date, as new states have been added to the program, 2.1 million more new prescriptions have been filled in those states as compared to the same time periods last year.” If true, then Wal-Mart is increasing its average number of scripts per pharmacy by about 20% per store. I suspect that incremental costs for this additional volume are relatively low at Wal-Mart, making the program a financial win.

So far, no one has any real data on which chain or format is being affected by Wal-Mart. Most obviously, cash pay customers will switch first. Chains appear less vulnerable because customers with third-party insurance may not save very much versus standard co-pays.

However, chains are now in the awkward position of telling customer to ignore price, an argument that seems curiously at odds with the trend toward consumer-driven health care decision making. Walgreens (NYSE WAG) took the bait and issued a bizarre press release telling customers to focus on “convenient locations, close-in parking and unique pharmacy services.” Ouch. How long until CVS Corp (CVS) or Walgreens cave in and lower their generics margins? PBMs also risk a margin squeeze if payers question their generic dispensing profits versus Wal-Mart.

Bottom line: I stick by my prediction made when the plan was first announced in September: Wal-Mart's Generic Pricing Will Trigger Big Changes. My two criteria for the magnitude of the near-term impact were (a) how well Wal-Mart rolls out the program, and (b) how quickly (if ever) they include more mainstream generic products. (See Reconsidering Wal-Mart -- but just a little.) The national roll-out has been very fast. I predict generic Zoloft and Zocor are not far behind.

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

New York Times editors read this blog!

On Monday morning, I posted CMS as a PDP: A Part D compromise? suggesting a compromise on Part D that could avoid a Presidential veto:

"Medicare beneficiaries will have the option, but not the obligation, to enroll in a national plan based on directly negotiated prices. The current system of regional PDPs will remain, in effect putting the government into competition with private plans."

On Tuesday morning, The New York Times ran an editorial called Lowering Medicare Drug Prices, which states:

"The approach that most appeals to us would direct the secretary of health and human services to set up one or more government-operated drug plans to compete with the private plans. "

Interesting coincidence, don't you think?

Monday, November 13, 2006

The FDA on PDMA

The FDA released its final Compliance Policy Guide (CPG) and PDMA Q&A this morning shortly after Acting FDA Commissioner Andrew von Eschenbach addressed the conference. (All documents are available from the FDA’s new PDMA Resources page.) Ilisa Bernstein, Director of Pharmacy Affairs at FDA, also gave a presentation describing the Q&A.

Naturally, it’s a treat to hear directly from the FDA on the day new guidelines are released, even if the comments did not stray too far from the published documents. Here are three points that I took away from the presentations:

- No more stays – The PDMA will be implemented on December 1, 2006. Dr. von Eschenbach indicated that the agency is considering no further stays, casting serious doubt on the legal actions being pursued by some secondary drug wholesalers. (See my earlier post Channel Conflict as Pedigree Looms.)

- “Some must…all should” – Both FDA officials used the phrase “some must … all should” in their respective presentations. The PDMA excludes manufacturers and Authorized Distributors of Record (ADR) from the requirement to provide pedigree. To my ears, the phrase “… all should” indicates that the FDA does not want to see the ADR exclusion become a loophole to avoid pedigree.

- Manufacturers gain leverage – The PDMA makes ADR designation more important. Manufacturers could use the concept of a “written agreement” associated with an ADR to enshrine supply chain business requirements that might otherwise be covered in fee-for-service or distribution service agreements. I predict that ADR agreements will play a role in the next round of fee-for-service negotiations.

In my last PDMA post, I speculated on three possible outcomes from the PDMA:

- Wholesalers with an ADR relationship will pick up volume.

- Manufacturers will broaden their ADR networks.

- The marketplace will create a solution for pedigree.

Mark Parrish, newly appointed as CEO of Healthcare Supply Chain Services at Cardinal Health Inc (CAH), stated at the conference that Cardinal will continue to service some of its existing secondary wholesaler customers after December 1. AmerisourceBergen Corp. (ABC) highlighted its intention to provide pedigrees in a press release this afternoon. ABC noted that “…customers are charged fees that allow the Company to recover the cost of generating the pedigrees.” (I’ve heard that the monthly pedigree service fee is $5,000 for the first ship-to location, and $1,000 for each additional location.)

RFI-Do or RFI-Don’t?

Dr. von Eschenbach said that track-and-trace means "from the assembly line to the dispenser." Unfortunately, this year's RFID conference has once again provided little substance on the use of RFID by pharmacies to authenticate inbound product.

This is the major unspoken limitation in using RFID to make the supply chain more secure: How do we stop pharmacy buyers and consumers from purchasing outside of a theoretically secure supply chain? I refer to this challenge as Our Demand Side Counterfeit Drug Problem. It's the pachyderm in the parlor. And unless we start getting real about this problem, then we won't really be meeting the FDA's needs or securing the supply chain.

CMS as a PDP: A Part D compromise?

Despite these logical arguments, “Direct negotiations” has a simple, populist appeal that is hard to ignore. Just consider the fact that the issue was only narrowly defeated in a Republican-controlled House and Senate. (See my July post The Part D direct negotiations movement for background.)

I predict that a new compromise will emerge to avoid the prospect of a Presidential veto. Here's a brief sketch of how it might work:

- Medicare beneficiaries will have the option, but not the obligation, to enroll in a national plan based on directly negotiated prices.

- The current system of regional PDPs will remain, in effect putting the government into competition with private plans.

- The government plan will receive an additional rebate analogous to the Medicaid rebate program, which seeks to ensure that Medicaid agencies pay the lowest (“best”) price available to any other customer.

Happy Jack

Part D has proven to be a very popular program, judging by the many polls on the topic. According to the latest poll from the Wall Street Journal and Harris Interactive:

- Three-quarters of enrollees say they are satisfied with the plan, compared with 24% who aren't satisfied.

- 70% say the plan has saved them money on prescription drugs, compared with 20% who say it hasn't.

- The plan has been easy to use, say 82% of respondents vs. 13% who disagree.

The Seeker

Yet the direct negotiations crowd ignores the risk that changing the structure will lower satisfaction by reducing choices. I worry that the Democrat’s emotional focus on squeezing a few theoretical pennies out of drug makers may blind them to this variety.

A big benefit of today’s structure is the choice created with the competitive system. I looked up the plans in my home zip code in Pennsylvania using CMS’ online Prescription Drug Plan Finder. I found 66 prescription plans for 2007 with monthly premiums ranging from $14.80 to $104.50 (average premium = $36). There is substantial variation in deductibles, cost sharing, and coverage in the gap. A national view is available in this handy summary from the Kaiser Foundation.

The range among my local 66 plans indicates that seniors have a lot of choices and can select a plan based on personal needs and individual situation. I suspect many seniors would not be happy in a one-size-fits-all plan. And as I pointed two weeks ago, direct negotiations may also throw the pharmacy industry into chaos and help Wal-Mart – true irony for Democrats! (See Are the Democrats helping Wal-Mart's Pharmacy?

If Medicare offered its own PDP, then the actual beneficiaries could decide whether the government's (presumably) lower prices are better than one of the other 66 options available. Seems fair to me.

It’s Not Enough

I also want to comment on the embedded assumption of direct negotiations -- lower pharma prices are automatically beneficial to society in the long run. This assumption is not as self-evident as it might appear.

To quote from the Amazon description of Richard Epstein's new book Overdose: “While critics of pharmaceutical companies call for ever more stringent controls on virtually every aspect of drug development and approval, Epstein cautions that the effect of such an approach will be to stifle pharmaceutical innovation and slow the delivery of beneficial treatments to the patients who need them.” (I am currently reading this dense, challenging book and will post a review sometime after my next long flight.)

Or as Peter Pitts as Drugwonks puts it: "to paraphrase Winston Churchill) our pharmaceutical patent system is the worst way to stimulate and support health care innovation – except for every other system." (See There’s a prize in every box!)

I recently attended a conference at which the keynote speaker made an off-hand remark that “drug prices are too expensive.” But as an economist, I must ask: “Too expensive compared to what?” Getting sick? Dying?

By all means, let's have a vigorous debate about how to make tough tradeoffs in health care. But is it naïve to think that mandating “lower” prices will not have unintended and potentially undesirable consequences.

Lunch is still not free.

---

P.S. Observant readers will recognize the subliminal plugs for my favorite new CD Endless Wire. Hope you buy before you get old!

Monday, November 06, 2006

CVS-Caremark: Why Now?

Today’s Wall Street Journal article on Tom Ryan’s background (CVS's Deal Maker Faces Toughest Test Integrating Caremark) alludes to some of the investor discontent, noting: “Some Caremark shareholders are grumbling that the purchase price is too low; some wonder if the sale is driven by weakness in Caremark's business.” In contrast, the original article from last week (CVS, Caremark Unite to Create Drug-Sale Giant) focuses on the conflict-of-interest issues because it was co-written by Barbara Martinez.

Below are the four hypotheses that I am hearing in my conversations. Vote for your favorite (anonymously, of course). If you choose "None of the Above," please add comment to this post with your preferred explanation.

Hypothesis 1: Why not?

Given the strategic rationale for channel compression, a deal was inevitable at some point in the next few years. (My take was posted on Thursday as Consolidation of the US Pharmaceutical Infrastructure). In brief, CVS has been trying to get closer to employers and payers with Pharmacare. At the same time, Caremark has become a major dispensing pharmacy through its mail order and specialty pharmacy activities. Why not now?

Hypothesis 2: Business Model of the Living Dead

The most common hypothesis, which I have heard repeatedly over the past few days, views the deal as a harbinger of change for the PBM business. By selling now (at a discount), Caremark is telling us something bad about future PBM business model, despite the Q3 results posted on Thursday. However, there is no consensus on the bad news to come. (Transparency? AWP? Lawsuit? Professor Plum in the Pharmacy with a Pestle?) This hypothesis helps to explain why Caremark was recently buying back its own shares at 20%+ more than CVS is paying now.

Hypothesis 3: Over the Hedge

Some argue that Caremark is sneaking out at the top, as Matthew Holt of The Health Care Blog suggests. This hypothesis is similar to the previous one, but does not contemplate the future revelation of hidden problems. Caremark’s stock bottomed out in the late 1990’s and is up 25X since then. Future sentiment looks more negative, so perhaps it was time to trade equity in a transactional intermediary for bricks-and-mortar and a strong consumer brand. (Shades of AOL/Time Warner!) One problem with this hypothesis is the fact that the stocks have performed similarly over the past two years. (See this Yahoo!Finance chart.)

Hypothesis 4: The Santa Clause

Over the weekend, I read an intriguing analysis by The Corporate Library arguing that the merger could trigger a change of control payment to Mac Crawford (Caremark’s Chairman, President, and CEO) of $17.6 million cash and $269 million in vested equity. However, the report also indicates that a lack of disclosure makes it hard to tell what’s really going on. Caremark’s board would not allow the deal to go through just because the CEO stands to get a big payout…right?

What do you think? ‘Tis the season, so cast your vote.

A technical note on voting: This survey prevents duplicate voting from the same domain in the same day. If you see a message indicating that you already voted, it means that the survey software can’t distinguish a unique IP address from your company. Sorry, ballot stuffers!

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Consolidation of the US Pharmaceutical Infrastructure

In my view, this deal represents a logical vertical integration within the U.S. pharmaceutical infrastructure – the network of companies that facilitate dispensing and payment of pharmaceuticals. It’s also the coverage area for this blog (which I called “Drug Channels” because it had fewer letters than the “Pharmaceutical Infrastructure Blog.”)

Channel Evolution

I have been studying how channels evolve for over 15 years. The following two guiding principles, which have motivated my research and consulting in many sectors of the US economy, can help explain the current deal.

- You can remove an intermediary but not the services provided by that intermediary. I am skeptical of the “PBMs add no value” critics because it is at odds with the marketplace realities. The PBM’s success reflects many individual business decisions by payers and insurers. If PBMs really added “no value,” then sophisticated payers would simply bypass them and perform the activity themselves. There are situations where this has occurred, but there has not yet been a rush for the exits.

- The services of an intermediary eventually migrate to the lowest cost provider of those services. PBMs heritage was in transaction processing, which was at one time a valuable service. As it became commoditized, they moved on to more complex services, such as formulary design. Like all intermediaries, innovative services often become part of core expectations, so further innovation is needed or disintermediation is at hand. Matthew Holt of The Helath Care Blog suggests that Caremark is sneaking out at the top, presumably because PBMs have reached the end of the line innovation-wise. I don't agree, as evidenced by the spirited debate that he and I are having over on his blog.

The confusion and uncertainty about the transaction stems from an inherent division of labor within U.S. Drug Channels. There are three major activity sets within this infrastructure:

- Product Movement from Manufacturer to Patient

Key intermediaries: Wholesalers, Retail Pharmacies, Mail Pharmacies, Providers - Payment flow from Patients/Payers to Manufacturers

Key intermediaries: PBMs, Insurers, HMOs, Government - Product Selection from Manufacturers to Physicians

Key Intermediaries: PBMs, HMOs

Big Unknowns

There is still much we don’t know about this deal, such as how the combined entity will work with other pharmacies to complete their retail network. See my comments in CVS/Caremark Creates Powerhouse, Unites Rivals:

But Fein adds that the fit could be awkward in other areas. In June, CVS acquired 700 Sav-On and Osco stores from Albertson's Inc. for $2.93 billion. While that helped the company solidify its national footprint, it still doesn't operate in all the markets covered by Caremark's dispensing network, which includes 60,000 retail outlets across the country. That network also includes a number of key rivals for CVS, among them Wal-Mart Stores Inc. (WMT) and Walgreen Co. (WAG).

"Strategically, Wal-Mart and Walgreen are going to have to make some tough decisions," Fein says. "I don't think they can sever their relationship with Caremark, because they need those customers. But they're going to be very nervous that Caremark could design programs that could favor CVS versus other programs.

Although the stock market doesn’t seem to love the CVS-Caremark deal, I still believe that it represents an inevitable compression of the industry.

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

CVS + Caremark: I called it!

But this news should not surprise faithful readers of this blog. Back on June 18, I explained the logic behind a PBM-Pharmacy Chain merger, arguing that control of the last mile in the pharmacy supply chain would lead to future chain pharmacy /PBM merger. Read my June analysis here: Walgreens' Future: I see dead canaries.

Although I was discussing Walgreens at the time, the same logic applies to a CVS-PBM combination. I wrote:

"The combined market cap of Medco, Caremark, and Express Scripts is roughly the same as Walgreens market cap. If PBM P/E ratios return to pre-2005 levels, they will be tempting targets for the retail chains."

Thanks to two unforseen events -- Wal-Mart and the AWP settlement-- valuations did drop, and look what happened!

See? This blog really can help you predict the future!

Tuesday, October 31, 2006

Channel Conflict as Pedigree Looms

Secondary drug wholesalers are planning to file an injunction against the FDA to stop implementation of the Prescription Drug Marketing Act (PDMA) according to this story from Drug Industry Daily. See Drug Wholesalers Seeking Injunction to Stop Drug Tracking Program.

By way of background, the FDA lifted the stay on implementation for the PDMA in June. It is now scheduled to be implemented on December 1, 2006. See my blog posts in the Pedigree category for more background on the issue as well as the FDA's Draft Compliance Policy.

I suppose that this filing was inevitable because the PDMA's Authorized Distributor of Record (ADR) system creates a powerful market dynamic toward a one-step channel. The extra costs and burdens of a two-or-more step (non-ADR) channel have the potential to shift volume among wholesale market participants. Speculatively, I imagine at least three possible outcomes from the PDMA:

- Wholesalers with an ADR relationship will pick up volume. The large wholesalers (MCK, CAH, ABC) will pick up volume from secondary drug wholesalers as well as physician distributors. Many med-surg distributors have found themselves caught between an ADR and a hard place. These companies often stock pharmaceuticals as a convenience for their physician customers but have relatively small volumes of Rx product in their mix (maybe 5% to 10% of total sales). They are not primarily secondary drug wholesalers, so need to either be ADRs or receive pedigree from a major wholesaler. For example, PSS World Medical issued a press release announcing its intent to buy directly from manufacturers after HB371 passed in Florida. (See PSS' Press Release.)

- Manufacturers will broaden their ADR networks. Contrary to popular belief, most pharma companies have authorized distributors beyond the big 3. The top eight manufacturers average of 79 ADRs according to published lists that I reviewed over the summer.

- The marketplace will create a solution for pedigree. A third option would be to allow the marketplace to determine winners and losers. If customers truly demand to purchase from a secondary wholesaler, then we can expect manufacturers to require ADRs to service those wholesalers. A manufacturer could even compensate an ADR for fulfillment to secondary distributors, making ADRs into de facto master wholesalers and possibly creating another area of fee-for-service compensation for wholesalers.

Unfortunately, I have heard only limited understanding of the ADR issue in my conversations with trade relations executives at pharma companies. The FDA is apparently issuing a Q&A next week to clarify the situation. In the meantime, the filing of this injunction should serve as a channel strategy wake-up call to manufacturers that have so far ignored the December 1 PDMA implementation deadline.

----

I have to go and get ready for trick-or-treating. I'm dressing up as something very scary -- a cute, cuddly teddy bear filled with counterfeit drugs! (See Items 7 and 10.) My kids are dressing up as RFID tags. Happy Halloween!

Thursday, October 26, 2006

Additional Comments on the AWP settlement

The $4 Billion Man

The October 6 Wall Street Journal article highlighted a $4 billion per year savings estimate. Anyone interested in this matter should spend some time reading through the underlying report to understand the assumptions behind the headline. (See Impact and Cost Savings of the First DataBank Settlement Agreement.)

In theory, a one-time adjustment to AWP will have a minimal impact as long as contracts can be renegotiated to preserve the original dollar-cost economic arrangements. So pay particular attention to footnote 19 on page 6, which provides Dr. Hartman’s reasons for believing that market participants will not be able to easily reverse the effect of the settlement with renegotiations.

Hartman’s viewpoints contrast with certain public statements, such as CVS’ press release: “In the event AWPs were suddenly reduced in a material way for particular products, obviously we would renegotiate the discount or dispensing fee. Virtually all of our commercial agreements are 'at-will' agreements, which can be renegotiated freely.” (See CVS Corporation Statement Regarding AWP.) Express Scripts was much more circumspect in its 10-Q filing this week, which created this week’s share price volatility.

Look Back in Anger?

We also don’t know the extent of look-back lawsuits against retail pharmacies by entities that are not part of the settlement class.

In reading the First DataBank court documents, I was struck by the fact that the First DataBank AWP settlement excludes all state and federal government payers from the settlement class. But 49 states use “discount from AWP” to compute Estimated Acquisition Cost (EAC) as the basis for pharmacy ingredient reimbursement under Medicaid. The median discount is 12% (range: -5% to -50%). Seven states have generic-specific formulas ranging from -20% to -50%.

Inflated AWP values would have also inflated Medicaid ingredient reimbursements to retail and mail pharmacies. Note that Medicaid rebates from manufacturers to the states are not affected because these rebates are computed based on Average Manufacturer Price and Best Price data.

On one hand, CVS’ comments on the relationship between negotiated discounts and AWP is consistent with the observation that we didn’t see windfall profits for pharmacy chains and PBM mail order in 2002. But reimbursement discounts did not widen for Medicaid EAC calculations. Will states make additional claims against retail pharmacies for Medicaid payments? Does this create financial/legal liability for the retail pharmacy industry?

And here’s a real brain-twister: How does the settlement affect the projected savings from the 2005 Deficit Reduction Act’s switch from AWP to AMP-based formulas? NACDS’ position paper notes that DRA switch reduces payments to community retail pharmacy by $6.3 billion over the next 5 years. (See Implications of Federal Medicaid Generic Drug Payment Reductions For State Policymakers.) If you believe Dr. Hartman’s analyses, about $2.5 billion of these savings will never materialize.

Looks like we’ll be living with the AWP settlement for a long time.

Friday, October 20, 2006

Are the Democrats helping Wal-Mart's Pharmacy?

The always-provocative Peter Pitts at the DrugWonks blog summarizes Pelosi’s plan very succinctly as The 100 Hour Reign of Terror. (Great title, Peter!)

Back in July, I warned about the risks facing pharmaceutical manufacturer and the drug channel (wholesalers, retailers, and PBMs) were the government allowed to negotiate directly with drug makers as part of Medicare. See The Part D direct negotiations movement. (Check out the “uncomfortable questions,” which have turned out to be good discussion-starters in planning sessions.)

Channel Impact

I’m not sure that direct negotiations could actually come to pass within the next 2 years given the prospect of a Presidential veto. But the post-2008 environment is certainly up for grabs, so let’s think through how direct negotiations would work.

A single-negotiator model would most likely lead to price-plus pharmacy reimbursement for Medicare Part D. In other words, reimbursement would be equal to the CMS’ negotiated “best price” or perhaps some variant of Average Manufacturer Price. PDPs would still be free to differentiate based on plan design and retail network breadth, maintaining elements of today’s market-driven plan approach.

This reimbursement model would cap the total revenue to be split among all channel players. In other words, price-plus reimbursement effectively caps the total compensation that can be earned by PDPs, retail pharmacy, wholesalers, PBMs, providers, and anyone else handling the product after it leaves the manufacturer’s factory.

Does Wal-Mart win?

The Part D winners in this scenario will be the low-cost channels providing a total dispensing and benefit management solution. For example, mail order fulfillment's relative efficiency versus retail dispensing helps PBMs sustain their value in the drug channel.

Ironically, the Democrat’s plan may also end up benefiting one of their current enemies -- Wal-Mart. Wal-Mart’s famed supply chain efficiency becomes a powerful weapon, especially if it is combined with a solid plan design. Imagine a Wal-Mart PDP, and all of sudden Wal-Mart’s recent attempts to build foot traffic in their pharmacy start to look much more strategic ... and certainly not the outcome that Nancy Pelosi expects.

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Dangerous Doses Redux

In case you don’t know, Katherine’s book Dangerous Doses is an outstanding piece of investigative journalism about how counterfeits entered U.S. drug channels, primarily in the period up to 2003. She documents how South Florida criminals exploited buyers in a then-vibrant secondary market. I highly recommend this book to anyone who wants to understand the mindset of counterfeiters in the pharmaceutical or medical products industry. It just came out in paperback with a new chapter. Here’s a link to Dangerous Doses at Amazon so you have no excuse for not buying it today.

Fortunately, much of the criminal activity that she describes in her book has been pushed out of the supply chain thanks to stricter wholesaler licensing, more secure business practices by manufacturers and wholesalers, and data sharing agreements that increase visibility. (See my previous post FDA blind to the supply chain’s evolution for more details on these changes.)

Katherine described a jaw-dropping exchange during her Congressional testimony last November (available here) in which one Congressman glowingly referred to diverters as “entrepreneurs.” Amazingly, the session had begun with Chairman Mark Souder stating: “The FDA confirmed with Subcommittee staff that drug diversion was the entry point for every case investigated by that agency involving counterfeit drugs going into legitimate pharmacies.”

But as readers of my blog know, our elected officials seem intent on encouraging diversion by opening new gateways for counterfeits. (My most recent rant was posted 2 weeks ago: A Big Win for ... Counterfeiters and Politicians?) Although Katherine and I don’t see eye to eye on every issue, we are in complete agreement that drug importation poses real risks. Check out her views here: Where Good and Bad Drugs Mix: Why drug importation poses real risks for American consumers.

IMHO, 2007 will provide more than enough material for Dangerous Doses II (Attack of the Clones?). The pharma industry needs to do a much better job of education because BuySafeDrugs.info just isn’t cutting it. In the meantime, feel free to send me your ideas on how we can turn the tide of public opinion. I’ll summarize the results in a future post.

Monday, October 16, 2006

Fixing American Health Care

I don’t share Mr. Holt’s implicit view that we should nationalize the health care system. However, I do like the way he highlights the important macro tradeoffs that will lock us into the current system for the foreseeable future.

On a lighter note, feel free to upload a video to ABC News if you have a solution that will “fix health care in America.” (Click the link -- this is a not a joke.)

The best solution will be chosen by Patrick Dempsey and Katharine Heigl from ABC’s hit medical drama Grey’s Anatomy. The winner gets to be Mark McClellan’s permanent replacement as Administrator for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (Bonus points if your DVD collection includes the "smart and sexy romantic comedy about the pharmaceutical industry" that starred Ms. Heigl.)

Thursday, October 12, 2006

Vote on Scenarios for Wal-Mart's Impact

Rather than telling you which scenario I think is most likely, let’s try a new experiment in interactivity with an anonymous poll. (Don't worry, I can’t identify individual responses, either.) There were more than 1,000 visitors to this blog in the past month, so I'm personally curious to see how many will vote.

SCENARIO 1: MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING

- Wal-Mart’s program is much more limited than initial media reports led people to believe.

- Generic blockbusters, such as Zocor, are not included. Most of the drugs are older, low volume generic drugs that are already inexpensive. Consumers will become disillusioned and disappointed as they realize the program’s limitations.

- The actual hard-dollar savings versus current generic co-payments are minimal for consumers with third-party coverage, creating very limited incentives for prescription switching. This strategy will only pick up a relatively small number of cash-pay customers.

- Adding blockbuster generics at $4 per script would be self-defeating because the gain in volume will not offset the loss to Wal-Mart’s earnings.

- Wal-Mart will never be as convenient as the large, well-run chains with premium locations (CVS and Walgreens).

SCENARIO 2: THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK

- Wal-Mart’s announcement is only the first step of a much larger plan to take pharmacy share away from supermarkets and independents. Evidence includes the national “Pharmacy at Wal-Mart” campaign, adding drive-through service, intriguing experiments that place pharmacy at the center of the store, and back-office software upgrades.

- Wal-Mart’s pharmacies are underutilized based on productivity metrics such as “number of prescriptions filled per pharmacy per week.” Most pharmacies can add incremental volume with minimal additional costs.

- Wal-Mart can build on its new position as the country’s large grocery retailer, placing pharmacy adjacent to food along the “main track” of the store. (Read about the Plano store in New, Upscale Wal-Mart Prototype Moves Pharmacy Centerstage.)

- The list will be broadened to include blockbuster generics as soon as the drugs pass the 180-day exclusivity period. While the PR boost will not match the initial September 22 announcement, Wal-Mart will price new generics to make them less expensive than co-payments.

- More seniors will begin paying out-of-pocket for prescriptions as they hit the donut hole. They will be price-sensitive cash-paying customers who will shift business to Wal-Mart.

Here's a final thought to keep us all humble: Confidence is the feeling you have before you fully understand the situation!

Wednesday, October 11, 2006

How Pharmacists View Wal-Mart's Pricing Strategy

Not really, judging by this article from Drug Benefit News. It includes everything from well-reasoned analyses to real head-scratchers like this one: “When they wag their tail, a hurricane starts in China.” Not sure why China matters when Wal-Mart is not even close to being the largest buyer of generics.

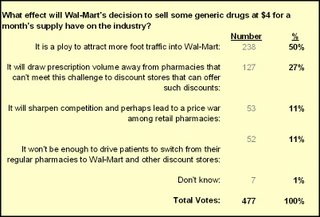

Nevertheless, the majority of pharmacists seem to think Wal-Mart will have an impact judging by Drug Topics’ online poll. Most readers of this magazine are pharmacists. In case the link breaks, here are the results as of 11 AM on October 11:

Granted, this is a highly unscientific poll. The pejorative framing of the question ensured that it would be first choice in the survey.

Yet more than half of the 477 respondents view Wal-Mart’s move as a “ploy” to drive store traffic. Note that they could have chosen “It won’t be enough to drive patients to switch…” Ploy or not, pharmacists are saying that Wal-Mart’s move will drive foot traffic. Today's WSJ-Harris poll indicates that Americans Likely Will Seek Low-Priced Generic Drugs At Discount Retail Chains -- so it looks like the pharmacists might be correct.

BTW, why did anyone in the pharmacist survey bother choosing “Don’t Know?” It’s an online poll, not the Spanish Inquisition! After all, nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition...

Friday, October 06, 2006

AWP Ain’t What Matters

Today’s WSJ article highlights one more reason why government reimbursement for pharmaceuticals is migrating toward methods that use actual transaction prices to approximate pharmacy acquisition costs. For example, the Federal Upper Limit for Medicaid pharmacy reimbursement will be AMP+250% for generics.

I predict that private payers will migrate to AMP-based pharmacy reimbursement, with many follow-on consequences for wholesalers, PBMs, and pharmacies. (See McClellan and the Magic AMP.)

The Law for Averages

The article states that there were only two First DataBank employees who were trained to collect and update information. I guess the math was pretty easy since First DataBank only “surveyed” one wholesaler (McKesson) to “calculate” an average price!

Calculating a meaningful average is a lot harder when it requires more than just typing one company’s price list into the computer. (Ouch, that’s a cheap shot!) Check out the comments attached to the OIG’s June report on AMP, which highlights the real-world complexities of lagged price concessions, volume purchasing, price restatements, and many other technical computation issues.

The Waiting Game

As a result, I doubt that AMP will be implemented on January 1, 2007. Mark McClellan implied a delay when he said (in September) that “…within a few months CMS will publish a proposed revised definition of AMP.” (Source: Popularity of Generics Behind Lower Costs For Medicare Part D Benefit, McClellan Says). I’m very skeptical that CMS could release a new definition and then implement a few weeks later.

January 1 has not been a historically auspicious launch date for CMS initiatives. As someone named Howard Newton said: “People forget how fast you did a job, but they remember how well you did it.”

My corollary: If you do it well, then you are less likely to be sued and appear on the front page of the Wall Street Journal.

Thursday, October 05, 2006

A Big Win for ... Counterfeiters and Politicians?

This new policy is great news for two groups: (1) the counterfeit drug industry, and (2) politicians up for re-election.

Manufacturers will surely begin monitoring their shipments even more closely in order to allocate available quantities of their products based on actual prescription demand. Very reasonable and a sound supply chain policy.

So where will Canadian pharmacies source their products from? Hopefully not from these guys, but we'll never know for sure, will we? You may recall that Mediplan’s founder would not say where he gets his drugs after the FDA's August warning in August. (See my 9/4 post Our Demand Side Counterfeit Drug Problem.)

By the way, our neighbors up north are not happy either. The Executive Director of the Canadian Pharmacists Association said "We can't afford to be the medicine cabinet for the U.S." (Read this good article from CBC News: Canada shouldn't be 'medicine cabinet' for U.S., pharmacists warn.)

Then again, Canadians don't vote in mid-term elections, unlike the 80% of Americans who favor importation in this Harris/WSJ poll.

Strange days indeed...

Thursday, September 28, 2006

Pfizer's UK Deal: Change is Here!

Pfizer just announced the consolidation of UK product distribution with the retail/wholesaler Alliance Unichem. (See "Drug giant will sell direct to beat the counterfeiters.") Since the agreement is described as "direct," I presume that it is an agency agreement -- a pure non-margin fee-for-service model.

The Unichem move solves two related problems bedeviling Pfizer:

- The lost revenue from parallel importing -- According to GIRP data, about 75% of drugs are delivered by full-line wholesalers while 16% are from "short-line wholesalers" a.k.a. parallel importers. (See Curious about European Drug Distribution? for more on the EU channels.

- The risk of counterfeits entering the supply chain -- I wrote about Pfizer's Lipitor problems in my August post London Calling: Fake Drugs Get Real.

Free market innovation has already improved the safety and security of the US drug distribution channel. (See my June post FDA blind to the supply chain’s evolution.) Looks like the market will evolve in the EU even sooner than I predicted!

A Partial Win for Glaxo Means More Change for EU Drug Channels

Well, Glaxo just won another victory. (See "Glaxo Partially Wins Fight In EU Court Over Pricing.")

Spain is one of the major sources of parallel exports in the EU. With this new ruling, the Court is once again recognizing that a manufacturer has the right to manage its own distribution channels. The Spanish ruling is not as clear cut because it merely pushes the decision back to the European Commission. This ruling will also benefit Pfizer, which had also been using a dual pricing strategy in Spain.

Diversion problems crop up anytime price variations between markets create arbitrage (buy low-sell high) opportunities. In the case of the drug channel, national pricing combined with EU's market integration principles created a flourishing grey market.

I predict that EU manufacturers will gain at least limited ability to implement dual pricing models in other exporting countries. This ruling will also provide a foundation for US manufacturers to attack diversion of products from the EU back to the US.

Mark Twain once said: "History doesn't repeat itself, but it rhymes." EU wholesalers should start learning words that rhyme with "transparency," "accountability," and "control."

Friday, September 22, 2006

Reconsidering Wal-Mart (but just a little)

Many analysts and news stories are rightly pointing out that yesterday’s Wal-Mart news was blown out of proportion once we all found out what Wal-Mart was really doing. In particular:

- The list includes multiple dosages of the same products, making the total closer to 130 rather than the advertised “300 drugs.”

- The list excludes blockbuster generics, such as Zocor and Zoloft

- Many of the drugs are older, low volume generic drugs that are already inexpensive

- The program is only being offered in 65 stores, with future roll-out plans uncertain

These are all valid points about the program that was actually announced (versus what the mainstream media reported).

Nevertheless, I stand by my comments from yesterday arguing that Wal-Mart's generic pricing will trigger big changes. I elaborated on these remarks with Dinah Brin of Dow Jones yesterday in her story “PBM, Drug Wholesaler Stocks Down On Wal-Mart News.”

Wal-Mart’s move, while less significant than it first appeared, represents a triggering event. The near-term impact will be determined by (a) how well Wal-Mart rolls out the program, and (b) how quickly (if ever) they include more mainstream generic products.

But the fact that this announcement dominated news and stock prices in the drug channels universe demonstrates the power of their idea. Wal-Mart clearly struck a powerful chord with people. They are signaling their intent to remove profits from the retail pharmacy industry, to the ultimate detriment of pharmacy chains and independents. I believe that we’ll look back and acknowledge September 21, 2006, as a turning point in retail pharmacy's evolution.

Thursday, September 21, 2006

Wal-Mart's Generic Pricing Will Trigger Big Changes

Yes, you heard right - less than a triple grande non-fat caramel machiatto at Starbuck’s! (So now, dear reader, you’ll know what to order when you meet me in person.) Check out Wal-Mart’s full announcement, which has some additional details.

Folks, we are witnessing a triggering event in real-time. I think Wal-Mart’s move will create massive change in the U.S. pharmaceutical distribution system because it threatens our current system of cross-subsidization.

In May, I pointed out that profits on generic drugs now subsidize the distribution of much more expensive branded pharmaceuticals. (Click here to read my original post.) All the major players in drug channels – PBMs, wholesalers, and retailers – generate higher profit margins and more profit dollars per script from generics. Wal-Mart has been anticipating this unbundling for some time, as indicated by the December 2004 testimony of Frank Segrave, then-VP of Wal-Mart’s Pharmacy division, which was titled “Medicaid Prescription Drug Reimbursement: Why The Government Pays Too Much.” (Subtle, huh?)

Wal-Mart began repositioning its pharmacy department with consumers this summer through the “Pharmacy at Wal-Mart” campaign. They need to convince consumers that a mass merchant pharmacy is just as good as the category killer chains (CVS and Walgreens), but more convenient for the one-stop shopping. By adding the price angle, Wal-Mart provides another benefit for consumers while simultaneously unbundling and attacking the profit streams of competitors and suppliers.

Some initial predictions:

Chain margins will shrink. Wal-Mart is really aiming at the big 3 pharmacy chains, essentially forcing them to blink and lower their margins on generics, too. CVS and Walgreens have less room to maneuver because pharmacy is the biggest chunk of revenues at the chains (70% at CVS, 65% at Walgreens) versus less than 10% at Wal-Mart. PBMs could also get caught in a margin squeeze if payers question their generic margins versus Wal-Mart. And some consumers may prefer to pay cash rather than processing through their benefit manager and paying a co-pay.

The consolidation of retail pharmacy will accelerate. Just look at what has happened to the retail grocery industry. Wal-Mart has used its proprietary distribution system to grab a nearly 20% share of U.S. retail grocery sales in only 10 years, triggering an intense shakeout among regional chains and independents grocers.

Wholesalers will suffer as independents fight for survival. Large chains purchase generics directly from manufacturers, while small chains and independent pharmacies purchase primarily through wholesalers. (Wal-Mart’s largest wholesaler for branded products did not mention any large chains when raving about its generic growth opportunities in June.) Wal-Mart’s move will shift generic market share away from independents, particularly in rural counties that have low chain pharmacy penetration. Recall that wholesalers and their customers will be splitting a maximum generic profit pie (AMP+250%) after Jan. 1. (See my June post on AMP.)

Manufacturers face tough fee-for-service negotiations in 2007. Large branded pharma manufacturers have been able to negotiate very good fee-for-service deals, due in part to wholesalers’ willingness to cross-subsidize services with higher margins from smaller branded companies and generics. I predict that the next round of fee-for-service negotiations will be much more contentious as wholesalers ask manufacturers to plug the gaps.

Check back in 18 months and I'll let you know whether my predictions came true.

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

Reimportation and Homeland Security are strange bedfellows

I'm clearly not wise in the ways of Washington because this debate seems foolish. Business practices have led to a sharp drop in secondary market activity in the U.S. (Drug Store News recently referred to pedigree as a "solution in search of a problem.")

So how does encouraging diversion increase our security? I've blogged about the problems of secondary markets often. Rather than repeating myself, just look at my posts under the Drug Counterfeiting topic category.

And file this DC debate under "Things that make you go ... Huh?"

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

Contrarian Views on RFID

I got some strongly worded emails about my post on RFID in supermarket pharmacies, especially my comment that "...we have a long way to go before this technology has any impact on supply chain security." (That quote was also highlighted by FDA News in their Blog Watch.)

For another contrarian viewpoint, read the fascinating article by Industry Week columnist Paul Faber called "RFID Market Continues To Move Sideways". His main points:

- "The major retail compliance initiatives are moving forward at a steady pace, but well below previous expectations/hype."

- "The innovations that we see due to RFID technology are still largely due to pursuit of realistic goals in custom projects that address a specific need and provide an unambiguous return on investment."

I find it hard to reconcile Mr. Chang's (self interested) optimism with the comments from outgoing Pfizer CEO Hank McKinnell, who said "RFID is not ready for prime time anywhere." Mr. McKinnell also notes that "It does give you control [up] to the first person you ship to. But if that person subdivides, or the pharmacist subdivides, you've lost control." (The whole interview is worth reading -- see the article in July's Pharmaceutical Executive magazine.)

I'll add that track-and-trace breaks down if the person decides not buy from a legitimate source, which is the topic of my popular post on our demand-side counterfeit drug problem.

The FDA and state legislatures are sincere in their interest to secure the pharmaceutical supply chain with track and trace technologies. But we should not let technology hype overcome the real world of patients and pharmacies. The law of unintended consequences will come back and bite us hard.

Then again, I fly over 100,000 miles per year yet I'm not allowed to bring toothpaste on a plane. I wonder how well things will work if we let a giant government bureaucracy take charge of a pharma supply chain track-and-trace database?

If you are brave, feel free to leave comments, rants, and flames in the comments below. If not, just email me directly.

Sunday, September 10, 2006

Supermarkets, RFID, and Wholesalers

First, some context:

- Supermarkets made up 12% of 2005 retail pharmacy sales dollars.

- Supermarkets dispensed 470 million prescriptions in 2005, which is up 170%since 1992. For comparison, mass merchants (like Wal-Mart and Costco) dispensed only 365 million prescriptions, up only 96% since 1992.

- The biggest supermarkets with pharmacies -- Kroger, Supervalu, Safeway, and Albertsons – equal more than half of all supermarket pharmacy spending.

- Pharmacy contributes 9% of total store sales, which is about double the percent of sales from 8 years ago. The industry average mix (of stores with and without pharmacy) is 3% of sales.

- The “median of the average gross margin” for the pharmacy department was 19.6%. I find this interesting because chain pharmacies do not release any information about pharmacy margins which I presume to be roughly comparable.

- No companies are using RFID at a store level, suggesting that we have a long way to go before this technology has any impact on supply chain security. Only 4.9% plan to implement the technology in the pharmacy. I remain skeptical about the uptake of RFID at the pharmacy level, even though it could be an important way to stop counterfeiting on the demand-side.

- The ongoing strength of supermarket pharmacy is good news for chain-oriented drug wholesalers such as Cardinal Health and McKesson. According to IMS channel data, supermarkets are much less likely to get bulk/warehouse deliveries from wholesalers than chain pharmacy. As I point out in my post about the Rite-Aid-Brooks/Eckerd deal, wholesalers have become dangerously dependent on low-margin deliveries to the warehouses of large retail pharmacy chains. Even supermarkets with good self-warehousing networks rely more on direct-store delivery since pharmacy is a minority of sales.